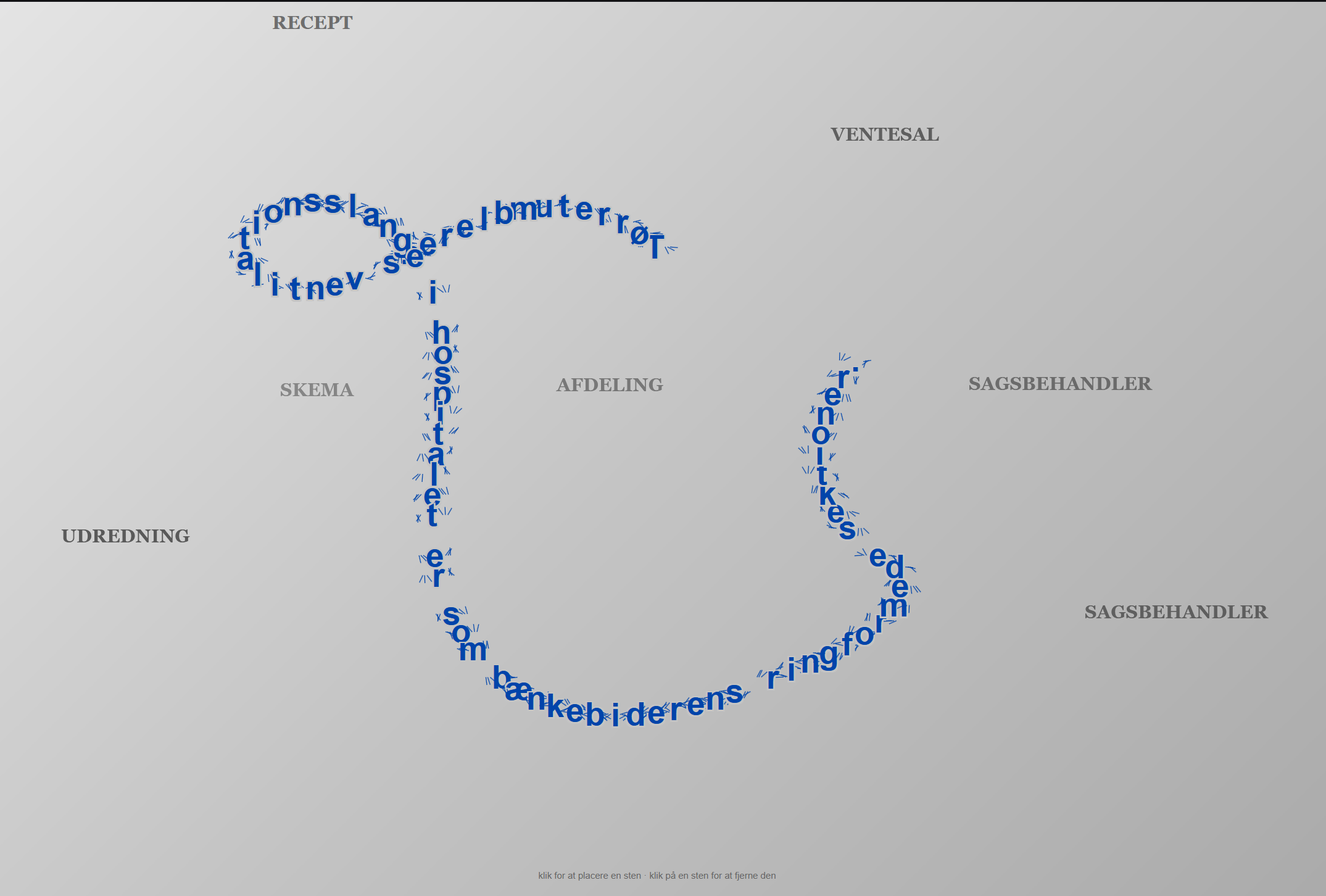

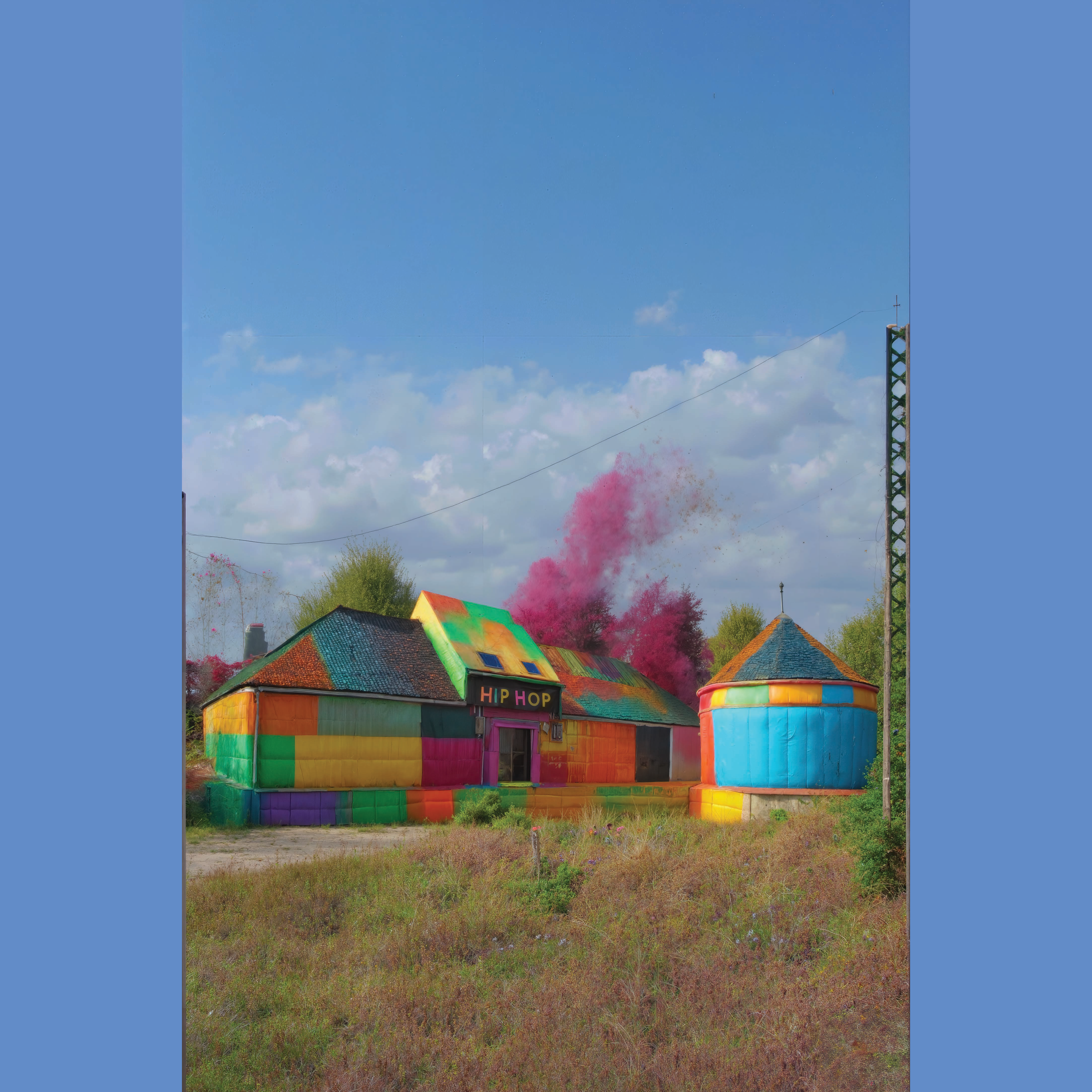

Leddyrsomsorg is a video piece using WAN 2.2 that imagines a future Danish healthcare system where giant blue woodlice and other arthropods have replaced AI and automation. The work will be shown at Ringsted Galleri in February 2026, with elements installed at Ringsted Sygehus. This split location is deliberate: the hospital setting places speculative images of care within the institutional architecture where care is actually administered, while the gallery provides a context for the work’s more discursive claims.

The work presents a welfare state utopia, a deliberately implausible scenario that sidesteps familiar debates about technology and care. It repurposes elements of “biophilic design,” where nature is organised to support recovery. But here, the organisms we rarely extend sympathy to have taken the place of therapy dogs or verdant parks.

The woodlouse (Oniscus asellus) is taxonomically distinct from the insects usually associated with infestation. Belonging to the order Isopoda within the class Malacostraca, they are terrestrial crustaceans–closer kin to lobsters than to the houseflies or wasps that typically trigger revulsion in local domestic contexts.

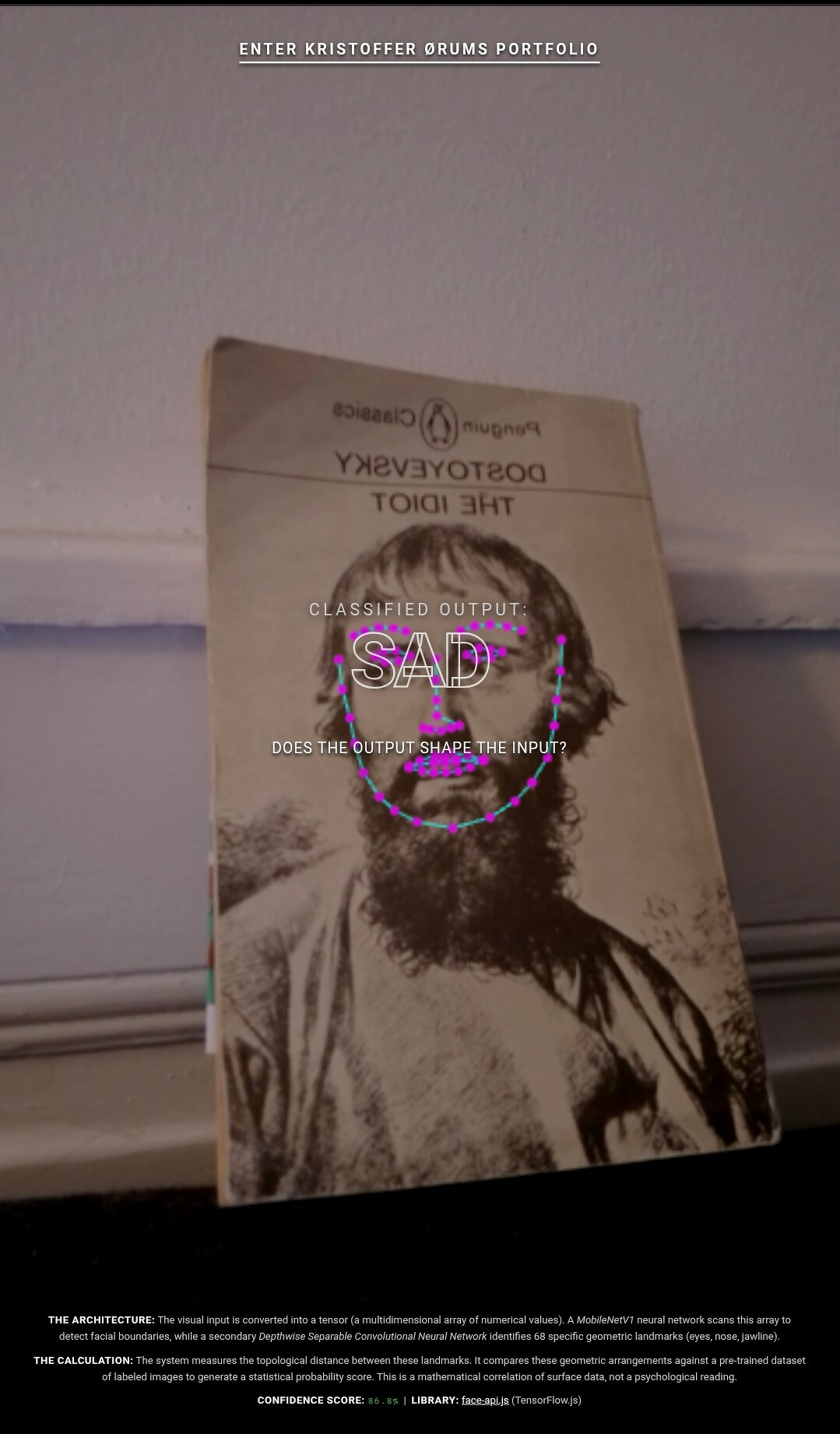

This biological nuance matters: we tend to normalise AI while immediately reading these crustaceans as alien. The work juxtaposes the high-trust, sterile aesthetic of Danish design–typically characterised by light woods and functional minimalism–with the chitinous, prehistoric movements of Isopoda. Both AI systems and these ancient crustaceans operate on logics that remain inhuman despite our attempts to domesticate them.

WAN 2.2 is a video generation model developed by Wand AI, a Chinese startup founded in 2024 by former ByteDance researchers. The model utilises a Diffusion Transformer (DiT) architecture, an approach that combines diffusion processes with transformer networks designed for temporal coherence.

The physical infrastructure underpinning this model is as significant as its software. Wand AI reportedly trained the model using thousands of NVIDIA H100 GPUs. Given strict US export bans on these chips, this represents a logistical feat involving the “grey market.” While the list price of an H100 is roughly $25,000 USD, reports from early 2025 indicate that prices within China fluctuate between $40,000 and $90,000 USD per unit. The volatility tracks sanction enforcement and supply-chain precarity. In that sense, every frame hints at infrastructure under pressure.

China’s AI development occurs within a distinct strategic framework, aiming for global leadership by 2030. However, for artists outside China, using a Chinese model involves navigating a specific hegemony defined by ideological boundaries. These models are subject to strict regulatory oversight, specifically the “Provisions on the Management of Algorithmic Recommendations” (2022) and the “Measures for the Management of Generative AI Services” (2023).

These regulations mandate that generative AI must not subvert state power, advocate the overthrow of the socialist system, or incite ethnic hatred. This creates censorship patterns distinct from Western commercial platforms. While US models filter content based on “brand safety” and legal liability, Chinese models filter for state-approved narratives. When prompting for complex social scenarios, one may find the model refuses to generate imagery suggesting civil unrest or specific political symbolism, not because of safety alignment, but due to Beijing’s stability mandates.

The concentration of AI development in the hands of a few giants creates an “AI Desert,” where universal models perform poorly on anything outside the dominant cultural hegemony. In some analyses, images from the US and Western Europe appear overrepresented in major training datasets like LAION-5B by up to a factor of 10 relative to their population. In several widely used facial datasets, white subjects comprise around 60–70%, while Black and Hispanic subjects often fall into the single digits. The woodlouse, with its segmented body and multiple legs, is not well represented in these datasets either. It does not fit the templates.

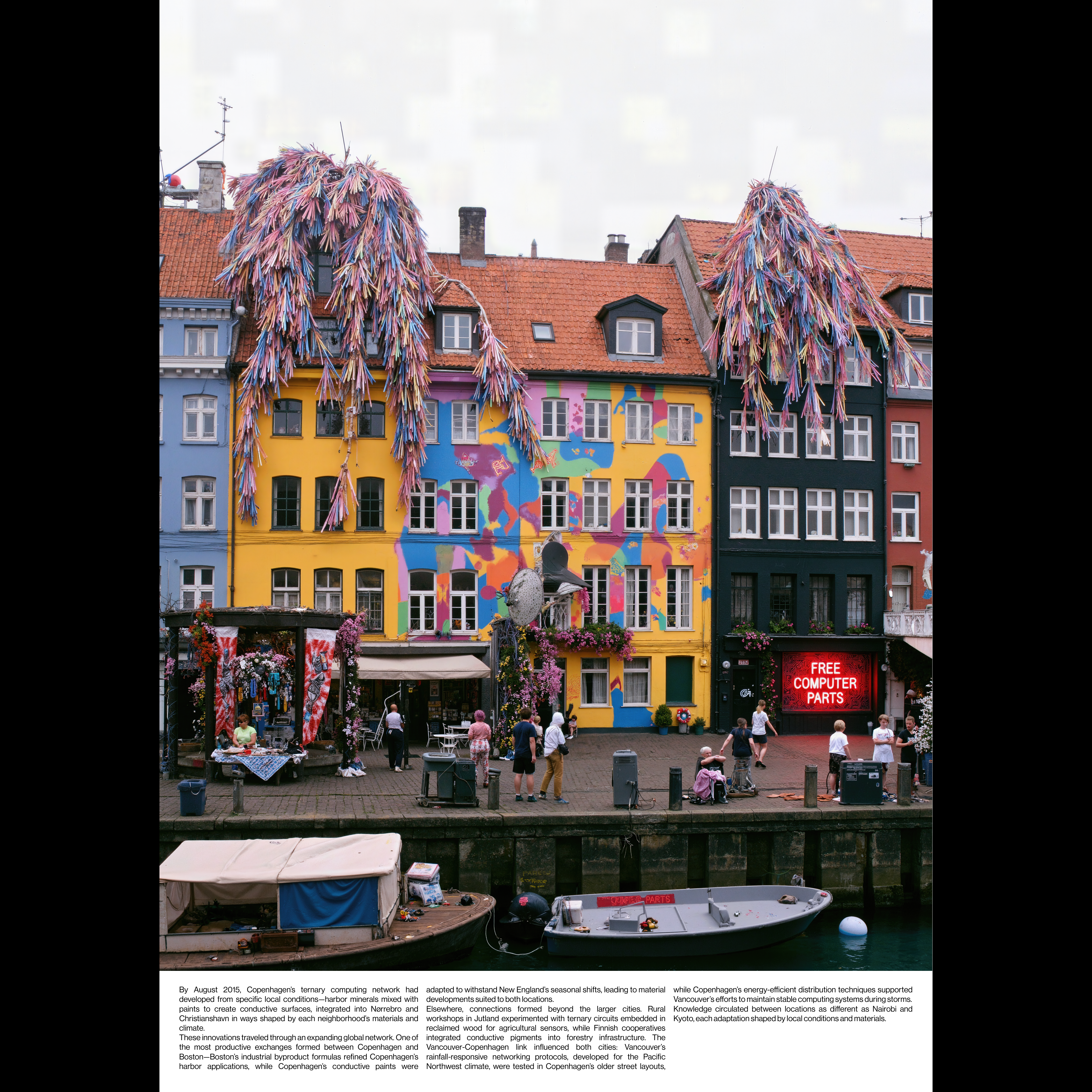

Linguistic bias is even more pronounced. The Common Crawl corpus, which underpins many foundation models, is approximately 45% English. Danish constitutes less than 0.1% of the total web corpus, and for smaller minority languages, representation drops below 0.01%, leaving them statistically marginal. A model trained on this data will struggle to render the specific spectral quality of the “blue hour” associated with the Skagen painters, or the precise cultural context of a local welfare centre, substituting them with generic, statistical averages derived from American or Chinese data.

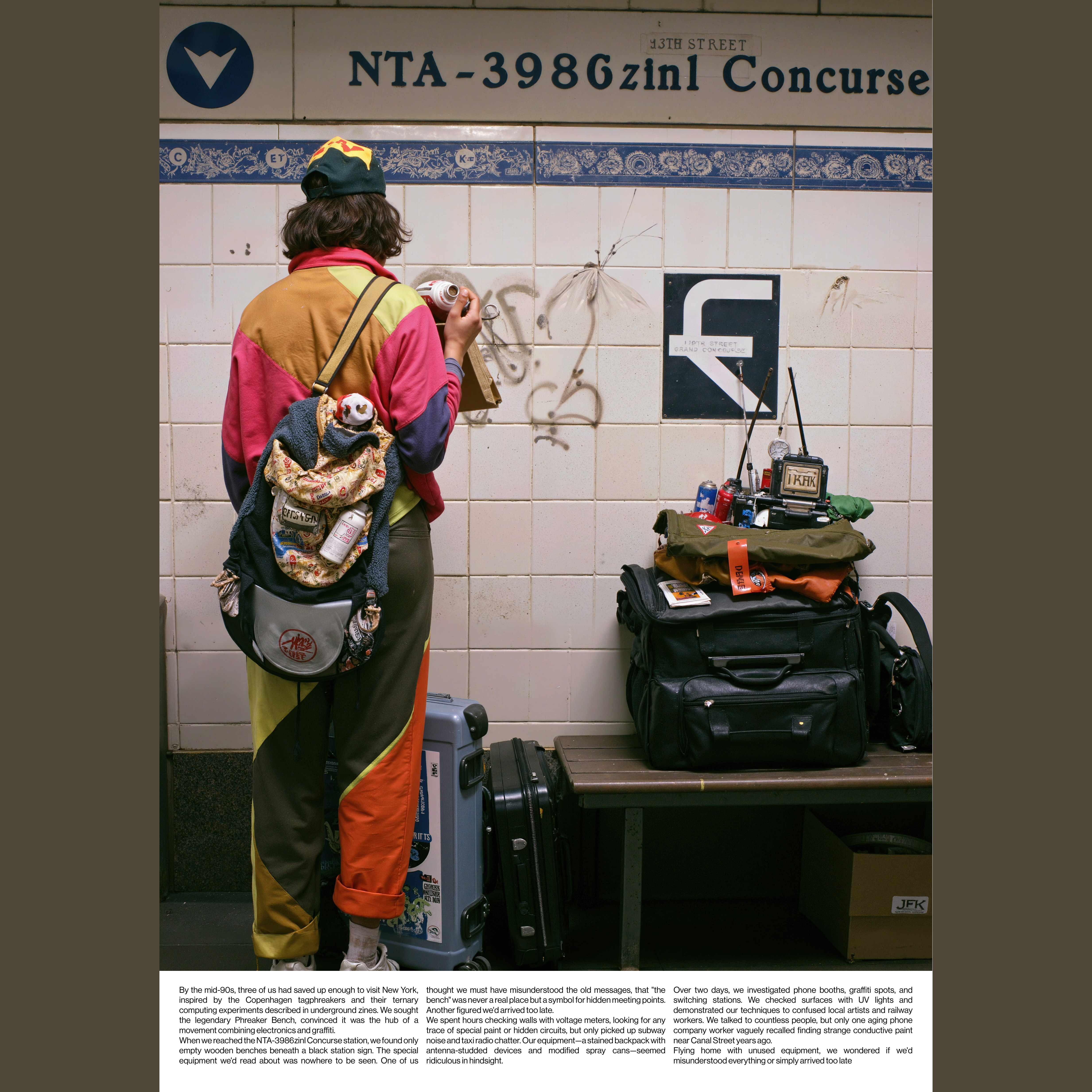

Most local artists will never consciously work with AI models. But their work will almost certainly pass through them: compressed, sorted, and subtly altered by systems baked into smartphone cameras, photo-editing software, and the content delivery networks through which nearly all images now travel. The question is not whether to engage with these systems but whether to do so knowingly. For those who choose to work with AI deliberately, the current situation demands a tactical manoeuvre: playing one hegemon against the other.

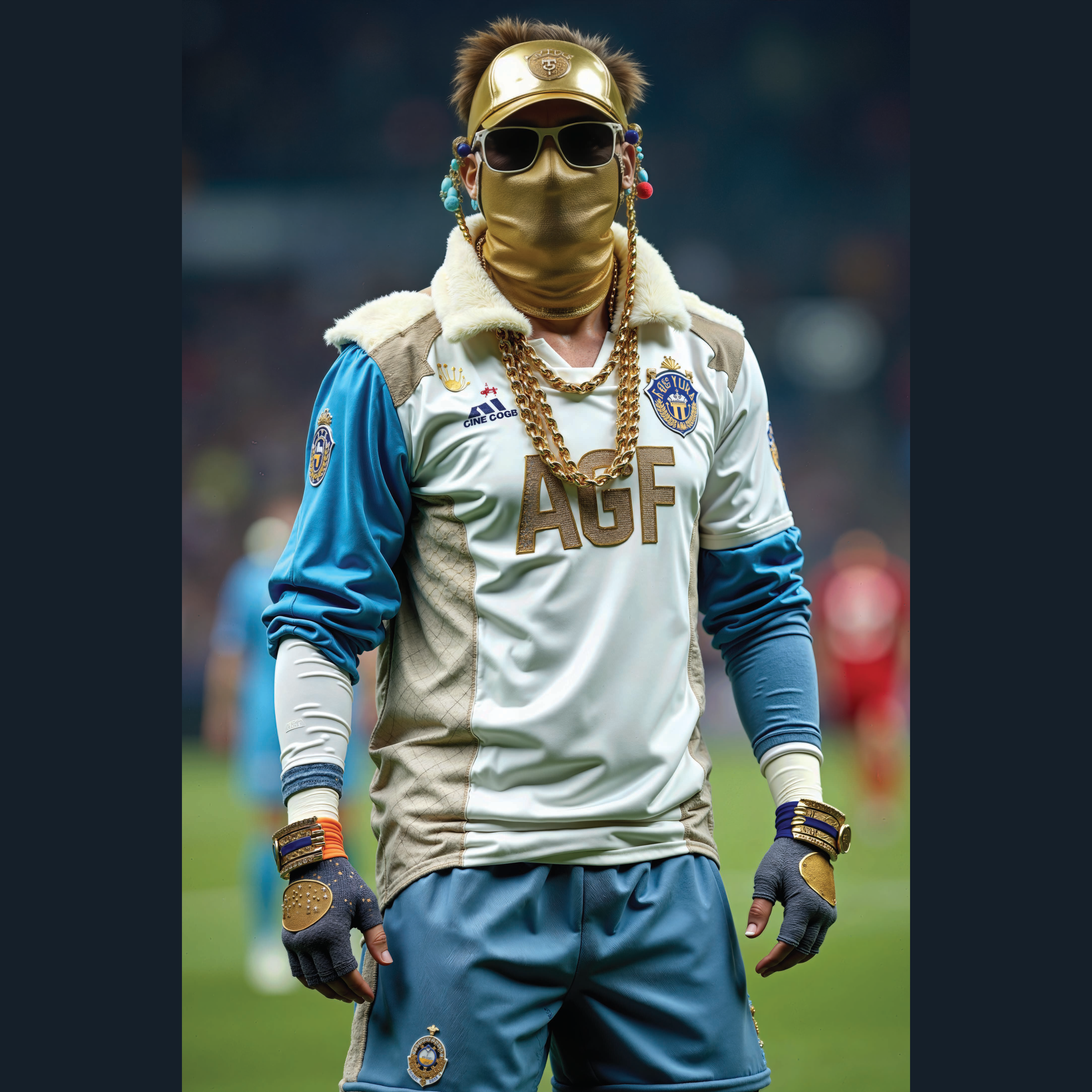

Using a Chinese model like WAN 2.2 becomes a way of jamming the signal of American cultural dominance. If US models like Sora function as the default standard–seamless, brand-safe, and template-like–then the Chinese model, with its distinct artifacts and ideological blind spots, offers a productive displacement.

Paradoxically, Chinese models often seem to render Danish landscapes more convincingly than their American counterparts. This is not because Wand AI trained on Vilhelm Hammershøi or the Skagen painters. The reason may be structural: northern China perhaps shares with Denmark a quality of flat, diffuse light, muted seasonal colour, and architectural scale that California simply does not possess. The brick and render of local residential buildings, the particular density of deciduous vegetation, the low horizons–these might find closer analogues in Heilongjiang or Shandong than in Los Angeles or Arizona. The American models, trained predominantly on data from a country where “good weather” means sunshine, tend to oversaturate and clarify excessively. They impose a Californian luminosity and default to timber-frame construction foreign to the local context. The Chinese models, perhaps inadvertently, may have absorbed a tonal range and built environment closer to the Baltic. The grey-green of a Danish beech forest in April, the particular flattening of depth on an overcast afternoon, the modest scale of welfare-state housing–these seem to emerge more readily from a model trained partly on images from northern China than from one trained on the American sunbelt.

Both systems aspire to universalism. The difference is one of familiarity. For someone raised within the American cultural sphere–and this includes most Danes under sixty–Hollywood’s visual grammar now feels natural because it is everywhere. We do not notice when a model defaults to three-point lighting or golden-hour warmth because these conventions have structured our expectations of what images should look like. Chinese visual defaults, by contrast, remain legible as defaults: the China Central Television aesthetic, the particular palette of state-produced historical dramas, the compositional habits of Weibo image culture. The Chinese model is no less hegemonic–it is simply a hegemony we can still see.

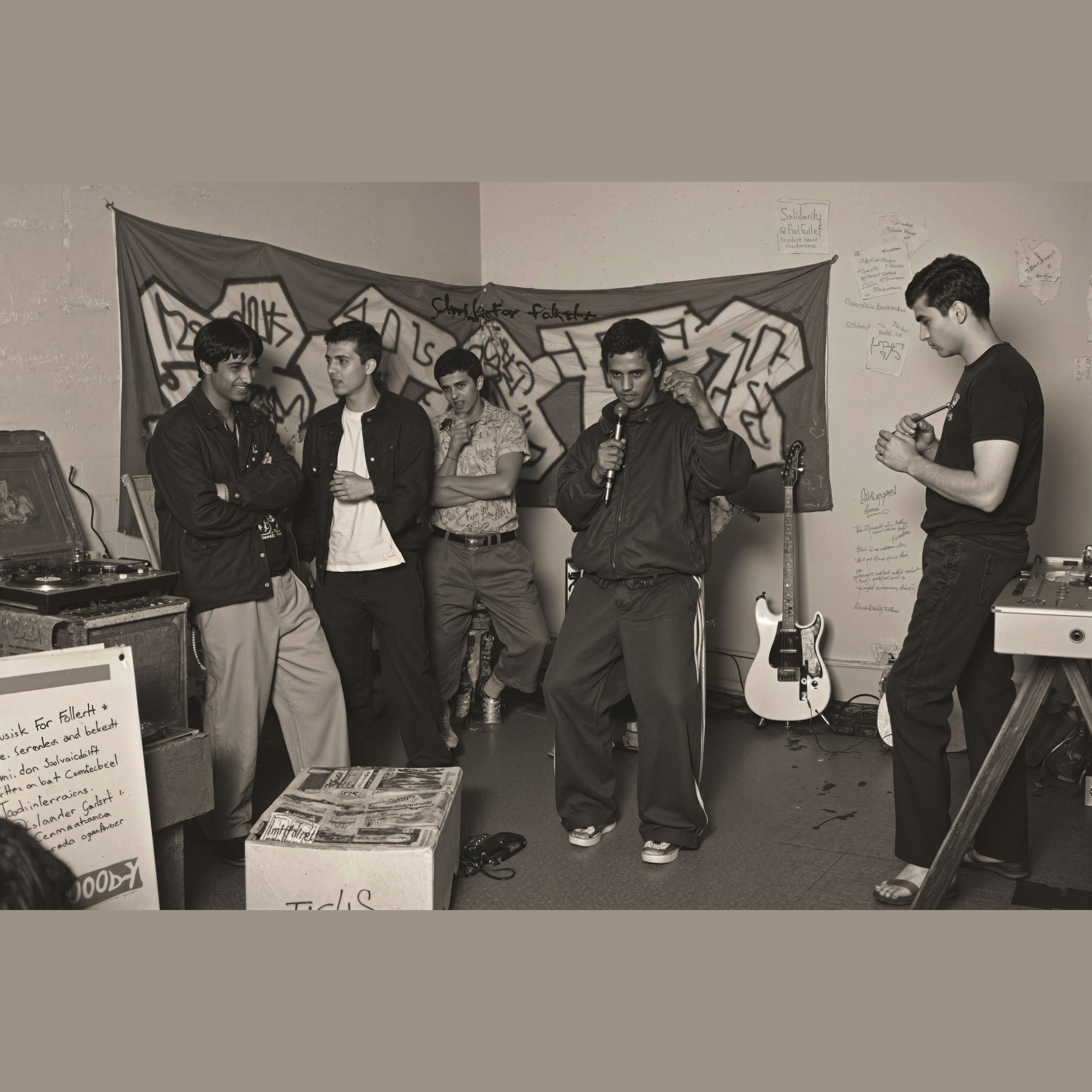

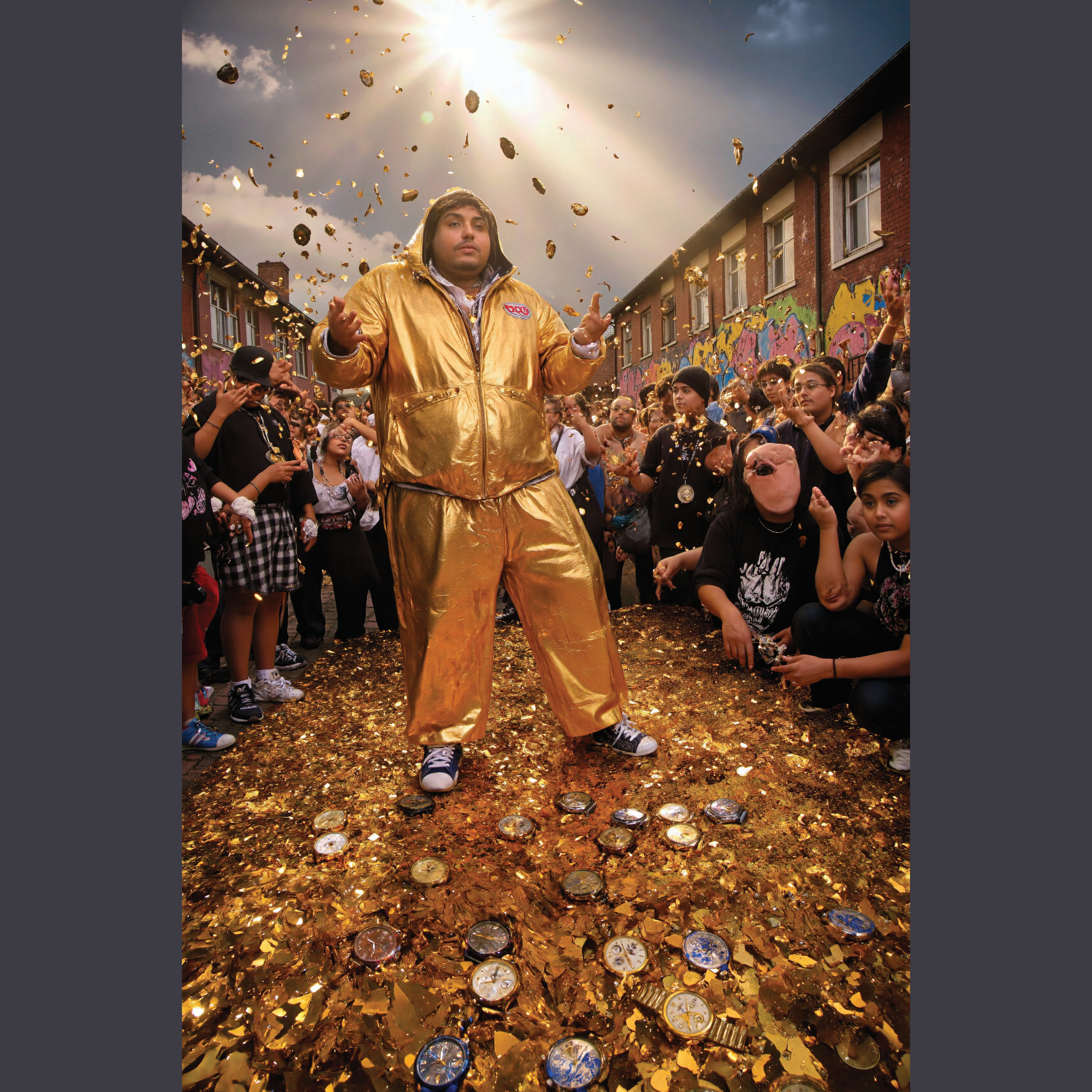

This is not to romanticise Chinese AI as a space of freedom. The constraints are real and different. When generating scenes of collective care, certain configurations of bodies trigger refusals; gatherings that might read as protest or unrest simply fail to render. But these constraints produce their own visual culture. Chinese internet platforms have long generated a rich tradition of mutating memes that circumvent censorship through visual substitution: Winnie the Pooh standing in for Xi Jinping, or the “Grass Mud Horse” (草泥马) whose name puns on a Mandarin obscenity. More recently, the character of Piglet has proliferated as a vessel for critique. His innocuous form carries meanings that evade algorithmic detection. These images thrive precisely because of the censorship apparatus, not despite it. Working within a Chinese model means inheriting something of this oblique visual logic, where meaning migrates into unexpected forms. The woodlice in Leddyrsomsorg function similarly: their innocuous, even repellent forms carry meanings the system was not trained to anticipate.

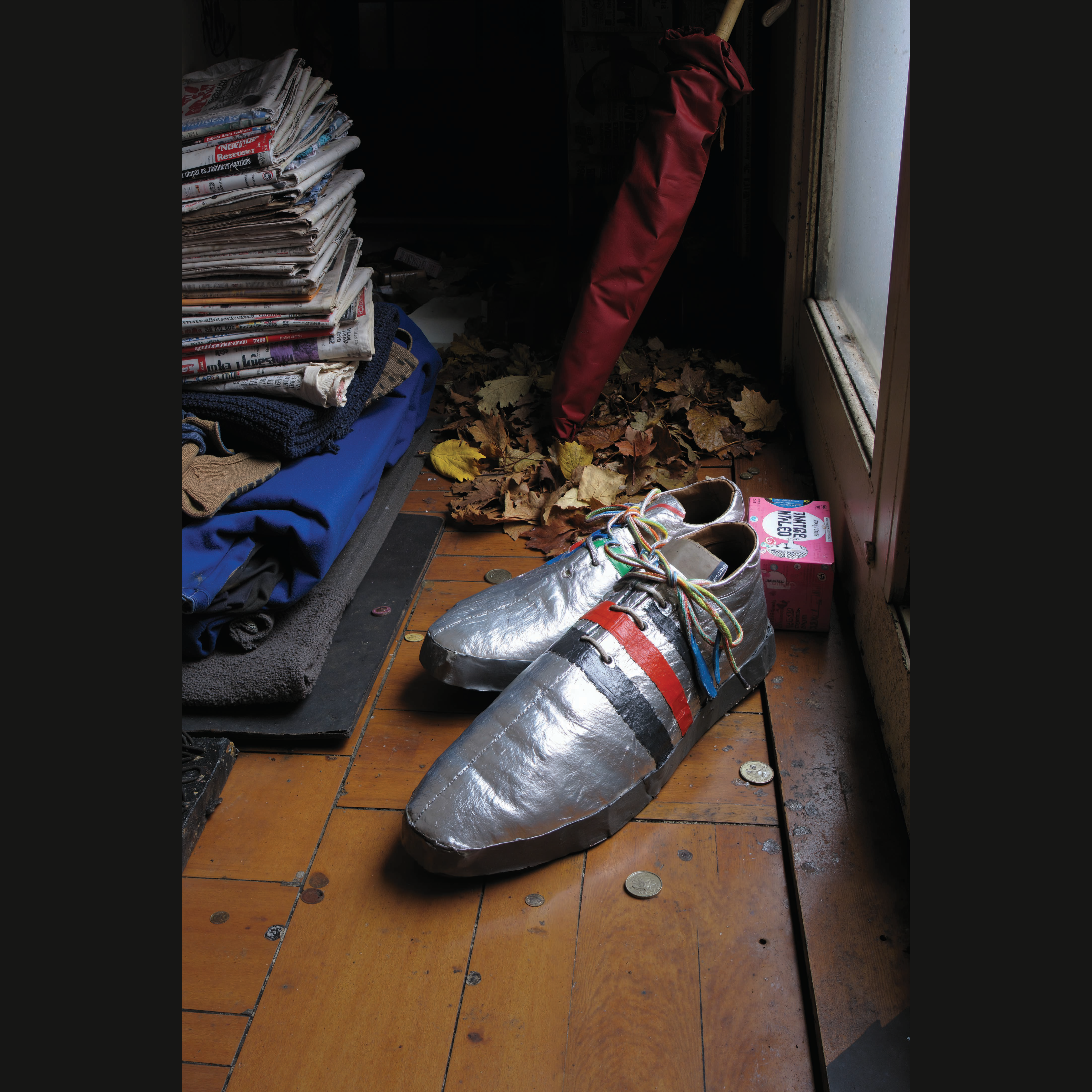

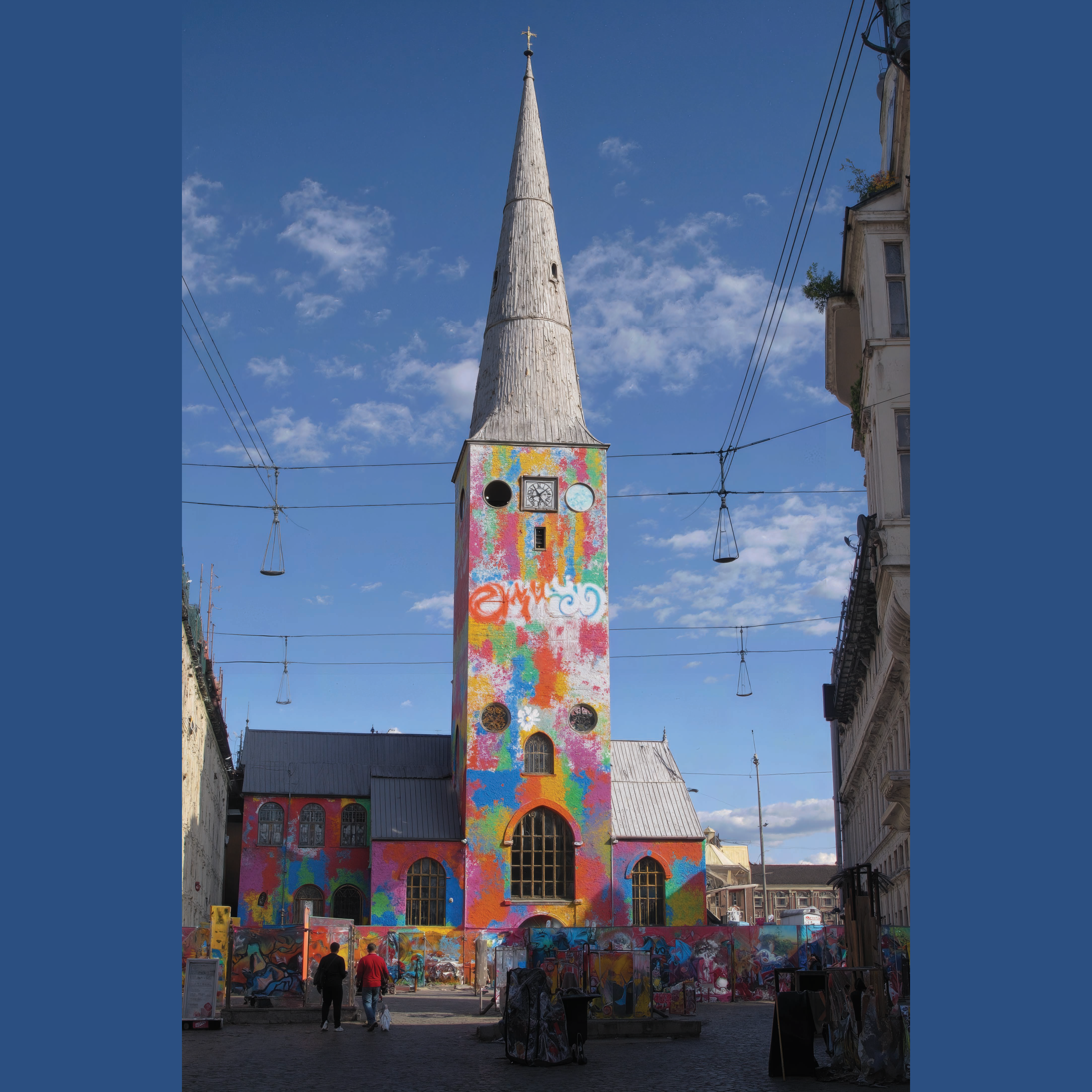

For a local artist, this obliqueness might resonate with certain habits of indirect speech. Denmark’s twentieth-century history includes moments where images and symbols carried meanings that could not be stated directly: the occupation-era practice of wearing red, white, and blue King’s Badges as silent resistance, or the tradition of singing national songs as collective defiance. More recently, the Danish cartoon crisis demonstrated how images become sites of geopolitical friction, their meanings multiplying beyond any author’s intention. Whether or not there is a coherent local tradition of coded communication, working with Chinese AI–with its own regime of prohibited and permitted images–places the artist in a structurally similar position: navigating constraint through indirection, producing meaning in the gaps.

The strategic value of this detour is temporary. It depends on the continued asymmetry between visual conventions that feel natural because they are everywhere and those that still register as foreign. As Chinese visual culture becomes more globally familiar–through TikTok, through the international circulation of Chinese cinema, through the sheer volume of AI-generated content flowing from these models–this window will close. The goal is not to remain permanently in orbit around Beijing any more than around San Francisco. It is to use the friction between these two gravitational fields to accelerate toward something else: local models trained on local archives, running on local infrastructure, producing images that do not need to be legible to either empire.

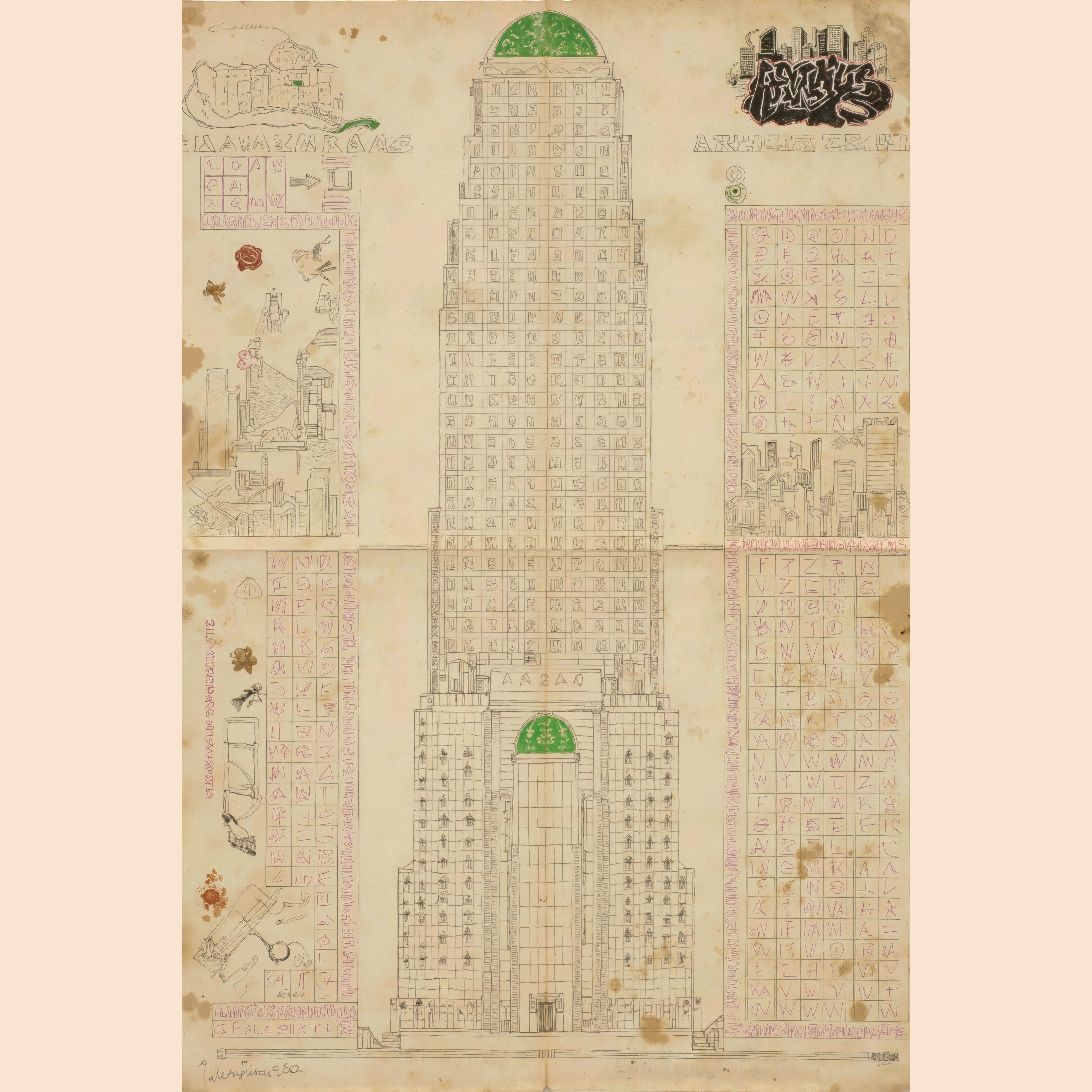

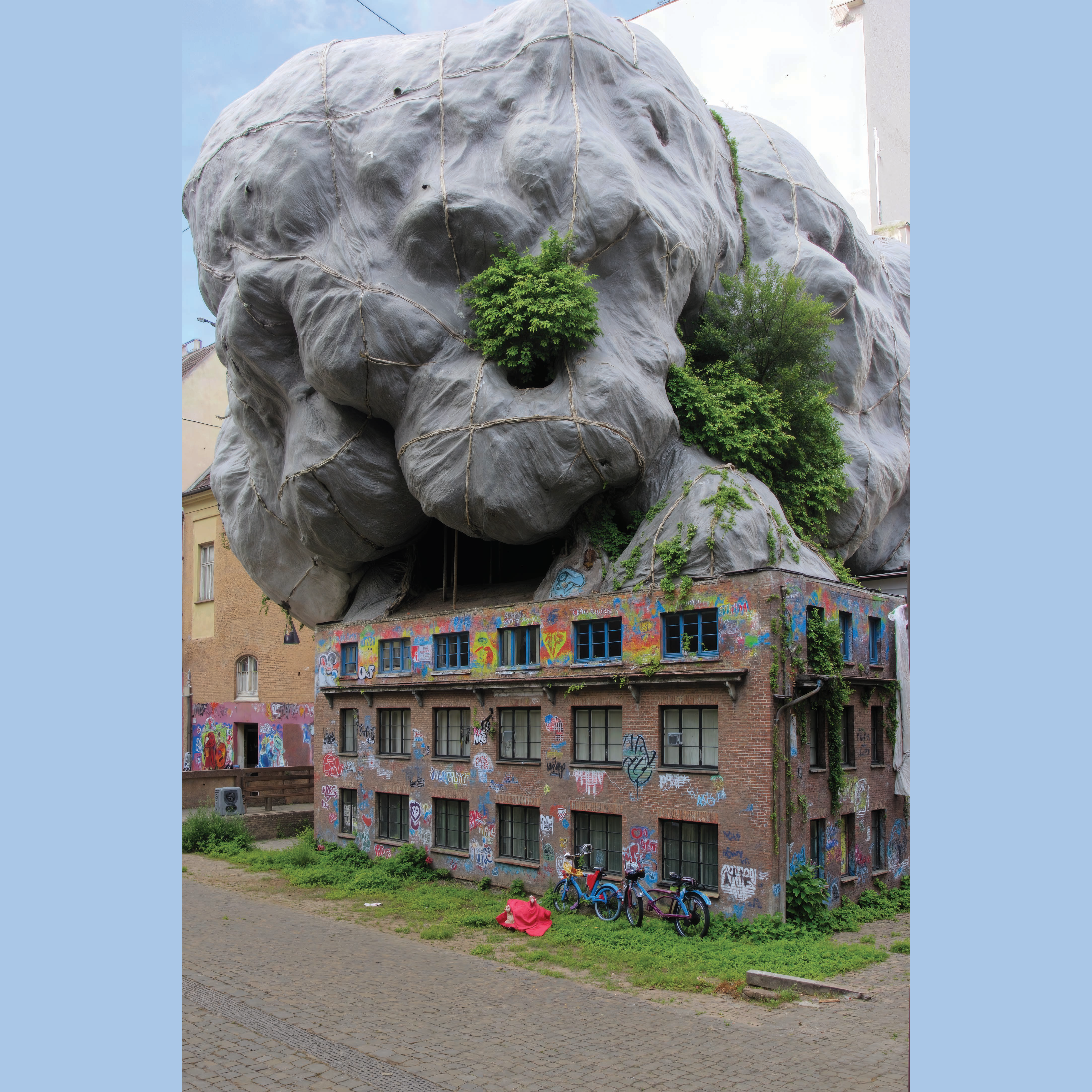

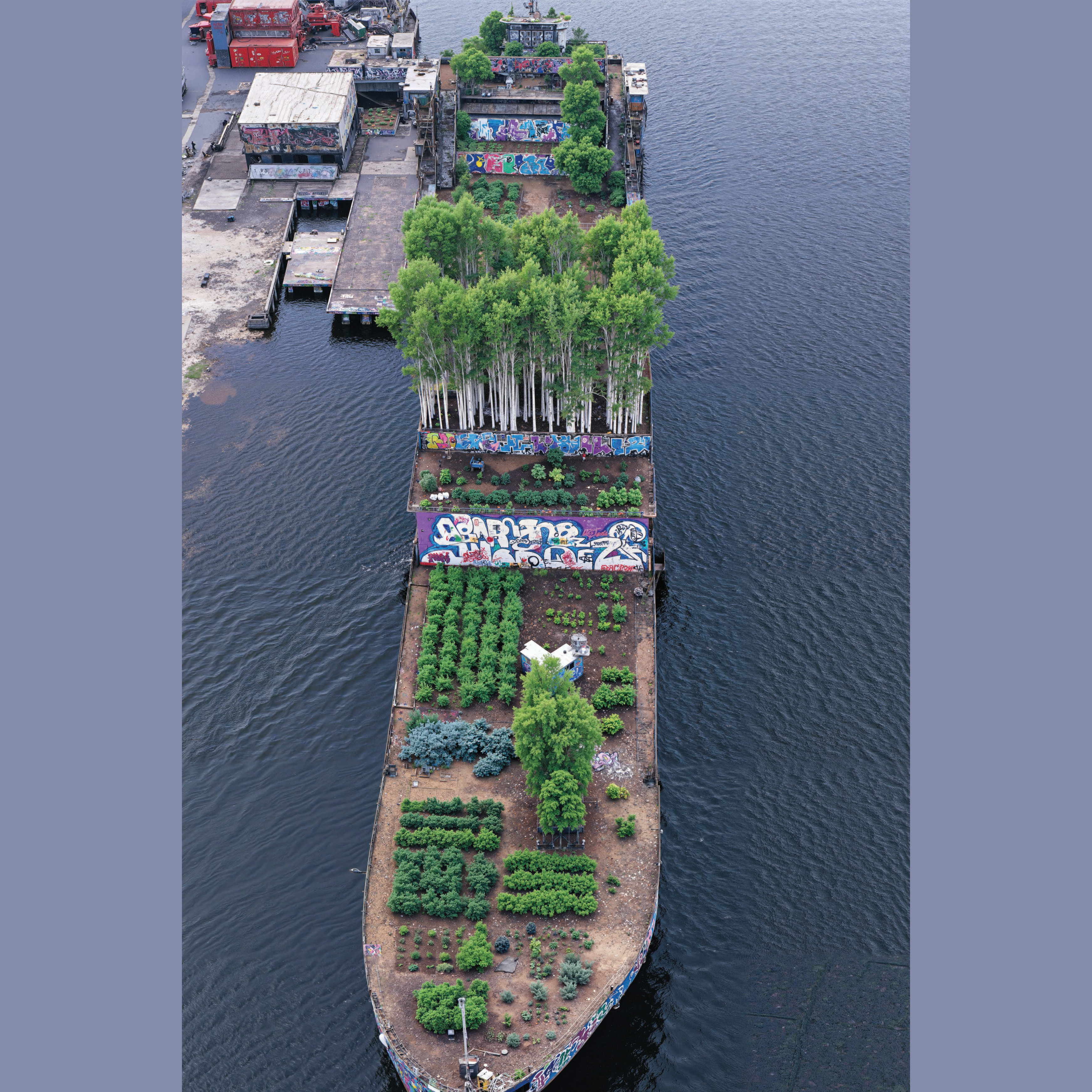

Ultimately, this detour points toward a future of distributed capacity. If local practitioners–historians, community archivists, artists–could fine-tune smaller, open-source models on highly specific datasets, the outputs would shift from generic approximations to culturally situated artifacts. A Danish cultural institution could train a model specifically on the Royal Danish Library’s photo archives, ensuring that historical dress, architectural vernacular, and local idioms are preserved rather than smoothed into global tropes.

What the detour through Chinese AI teaches, above all, is how dependence is produced at the infrastructural level. Running models locally forces smaller architectures and lower fidelity–consumer hardware with limited VRAM cannot support the trillion-parameter scale of the hegemonic models. But this constraint is also the condition of autonomy. Ivan Illich distinguished between tools that extend human capacity and those that create dependence on industrial systems and professional gatekeepers. A model requiring thousands of GPUs, procured through grey markets and cooled by data centres drawing megawatts, cannot be a convivial tool; it remains a service to which one submits. The local model, running on hardware one actually owns, recovers something Illich considered essential: the capacity to shape one’s means of production rather than consuming outputs defined elsewhere. The degraded image is the price of self-determination.

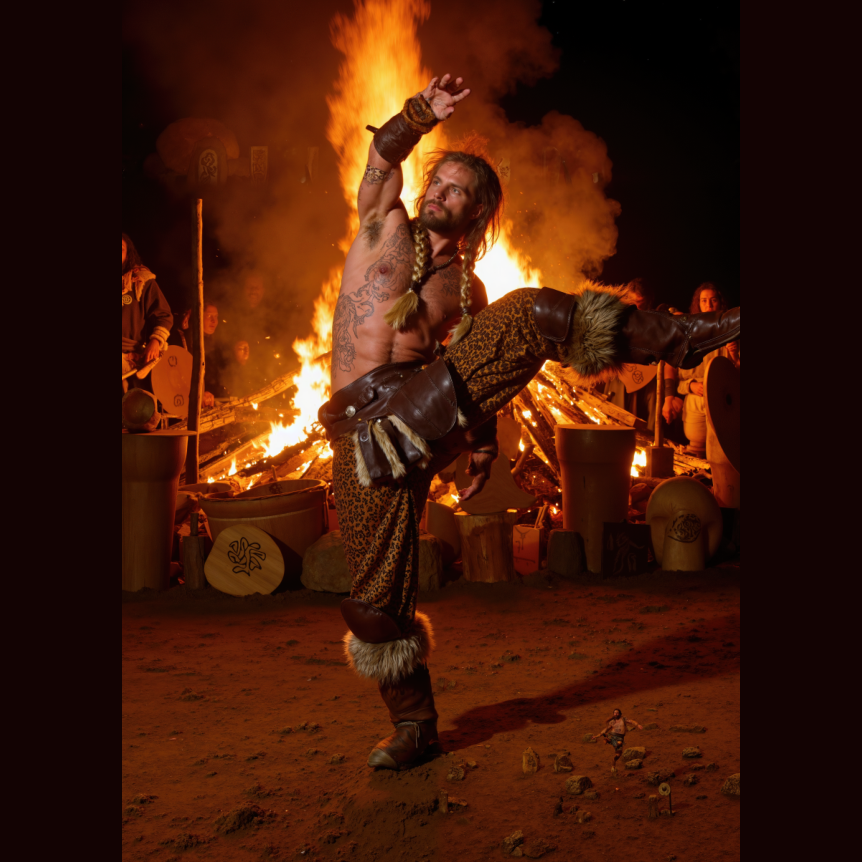

In Leddyrsomsorg, WAN 2.2 produces its own instabilities. Woodlice begin as woodlice but drift into insects; faces rearrange themselves when backs are turned; rooms reorganise as the camera pans. The model cannot hold its categories stable. What begins as a crustacean becomes an arthropod becomes something else, taxonomies dissolving in real time. This is not a failure to be corrected but a condition to be inhabited. The fluidity of signifiers–bodies, species, architectures shifting while remaining loosely recognisable–produces a dreamlike space where the boundaries that structure our thinking about care, nature, and technology become similarly unstable.

The model also produces bodies that depart from the norms of those who trained it: figures lacking arms, feet turned backwards, proportions that would be flagged as errors in any commercial context. But human bodies are wild and unruly. Our genetic mass produces extraordinary variation–variation that has been systematically excluded from the commercial photography these models learn to emulate. The training data encodes not human diversity but the narrow aesthetic of stock libraries and advertising campaigns. When the model “fails” to reproduce this narrowness, it inadvertently gestures toward the bodies that were never photographed, or never photographed approvingly. The so-called errors may sit closer to aspects of human variation than the polished outputs the model was trained to produce.

The woodlice do not represent an alternative to AI; they emerge from the same generative instability, their alien forms vibrating with the noise of a system that cannot decide what it is looking at, and perhaps should not be forced to decide.

We will have to live with AI systems as we live with woodlice in our basements: not as a choice but as a condition. The question is not how to avoid or eliminate them. Woodlice have been decomposing organic matter for three hundred million years; they will outlast our concerns about them. AI is now woven into the infrastructure through which images, text, and meaning circulate; it will not be uninvented. The question is how to inhabit these systems without letting them cause too much harm, and without causing too much harm through them. This is not a triumphant position. It is closer to the everyday pragmatics of damp management or repetitive strain: an ongoing negotiation with conditions that cannot be eliminated, only managed, mitigated, and sometimes resisted.

Nam June Paik once said he used technology in order to hate it more properly. The formulation is useful because it refuses the fantasy of critique from a clean outside. To hate something properly requires knowing its textures, its tolerances, the places where it gives. This text was proofread and spell-checked with the assistance of a large language model. The video it describes was generated by another. The critique of hegemonic AI systems is produced through hegemonic AI systems. This is not a contradiction to be resolved but a condition to be acknowledged. Implication is the starting point, not the failure. In Leddyrsomsorg, the woodlice are the form this implication takes: creatures that thrive in the damp, doing necessary work in spaces we would rather not look at.

Working tactically within hegemonic systems is how we learn to imagine building something else. The Danish welfare state itself emerged not from a sudden utopian rupture but from decades of compromise, negotiation, and the slow accumulation of small gains. If there is a future of local AI–models trained on local archives, running on local power, answerable to local needs–it will be built the same way: not by rejecting current systems outright, but by learning their textures and bias well enough to know where they give.

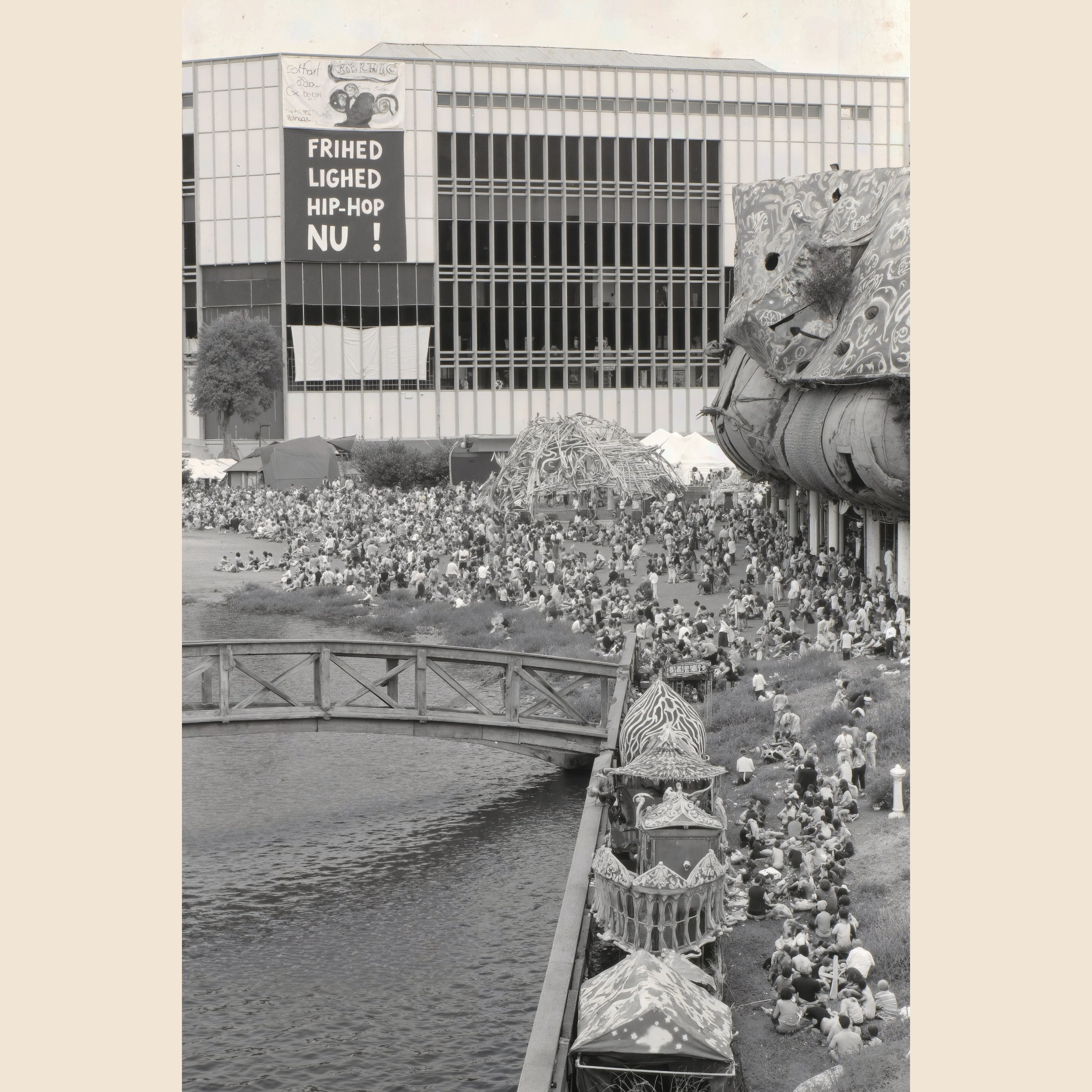

#FirhedLighedOgSymptom #WelfarestateMyths #SurealSocialRealism #ringstedsygehus #ringsted

Støttet at Statens Kunstfond